My first national championship appearance in 2015 has been archived in a previous blog post. I’ll be touching briefly on the ins and outs of the sport, however I encourage you to start with that tale for a more in-depth look at Olympic Weightlifting.

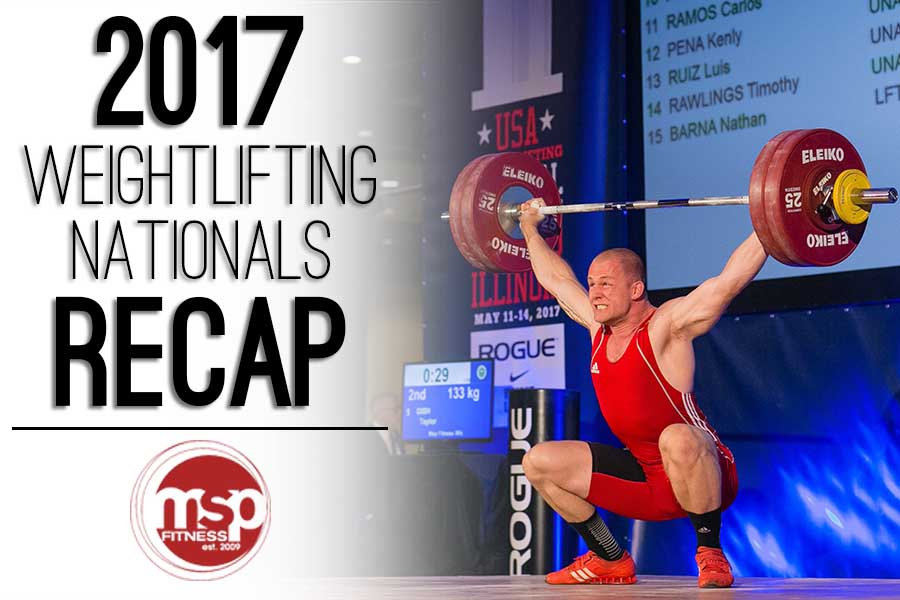

Processing any momentous event so close to the date of the experience can be tricky. As the storyteller’s exhilaration lingers, the recount runs the risk of being veiled in overly optimistic prose. In truth, what happened at Weightlifting Nationals a weekend or two ago in Chicago, IL was just a plan coming to fruition. And so, here’s my account.

The Lead Up

Coinciding with the birth of our second child, some significant changes were made to my physical training in the fall of 2016. For the bulk of my Weightlifting career, I’ve been graciously able to train on my terms — two hour sessions, four to five times a week, with plenty of sleep to augment my recovery. As responsibilities increased and priorities shifted, my time for training this cycle had been reduced to three, ninety minute sessions per week, occasionally performing a fourth hour long workout. While some readers might be thinking, “That lucky S.O.B. still gets to the gym 3x/week with two kids?!?!”, I note that it is not without an amazing support system I’ll be thanking later at the end of the post.

With these new adjustments, the early part of my 2017 training was consumed with the thought, “How do I continue to maintain, let alone progress, a high level of performance on less resources?” I was sleeping less, training less, and yet… I made improvements.

My coach Michael Pilhofer and I took a look at the time I had available and weighed our options. At the start of most previous cycles, we’d usually incorporate high volume work; exposing me to multiple repetitions on core lifts alongside a host of accessory movements. Those past strategies weren’t going to work this time because in training, the more you work, the more recovery you need. If a linear model, beginning with moderate intensity which increased to high intensity as volume dropped was unfeasible, what were we left with?

My coach Michael Pilhofer and I took a look at the time I had available and weighed our options. At the start of most previous cycles, we’d usually incorporate high volume work; exposing me to multiple repetitions on core lifts alongside a host of accessory movements. Those past strategies weren’t going to work this time because in training, the more you work, the more recovery you need. If a linear model, beginning with moderate intensity which increased to high intensity as volume dropped was unfeasible, what were we left with?

Much to probably both Michael and I’s reservations, our clearest option was to keep the volume relatively low and the intensity fairly high for the duration of the cycle. While it seems counter intuitive, there is less muscular fatigue experienced when training at a higher percentage of your maximum abilities. The nervous system receives more taxation under such a plan, but I was already planning on taking days of rest between workouts due to my schedule. On paper, low reps at tough weights seemed like the best way to go.

Some training lifts from early March. A miss and a make at 130kg

I can’t claim this approach would be perfect for everyone; in fact, I would likely steer clear with most athletes. To routinely perform at higher intensities, one’s technique needs to be solidified. Kid yourself all you want, but no one is learning anything or making changes based off cues given at such high loads. Think of it this way: when would it be best to practice your running technique? On a long-slow distance day, or on a tempo run? Or, worse yet, on a competition day? Changes to movement are made and cemented at low intensities. Fortunately, over the last four years of dedicating myself to this sport, my lifts have never been more put together technically. We might’ve been running this training plan with some risk, but thanks to all the foundational technique work, the high intensity plan came together beautifully and the training played out pretty flawlessly. I was ready.

The Meet

Schlepping a child-filled van seven hours down the road required some built-in buffer time. Knowing we wanted to get there and get acclimated, the family and I opted for leaving the Twin Cities Thursday, arriving in Chicago that evening. Once settled, I got in one last workout (just some light power snatches, power clean and jerks, and back squats) at the on-site training hall. After training was finished on Friday morning, I had a day and a half to chill and rest before I was set to lift on Sunday morning. As my wife can attest, traveling with a Weightlifter pre-competition isn’t very fun. As it is a weight class sport, many athletes can’t go and enjoy the local culinary fare and they don’t want to spend much time on their feet, as that can be draining. It’s kind of like vacationing with an depressed sloth. While I embody a more cheery outlook, my sloth-like tendencies cannot be denied.

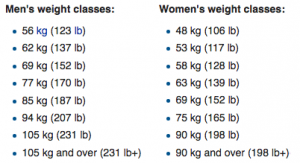

My session (Men’s 105kg “B”) was set for Sunday morning at 8:30am. The national meet actually began Friday with the lighter men and women competing in an ascending fashion based on body weight. Now, national meets are exclusive in nature. Athletes who desire to compete at that level need to hit a qualifying total within the qualification period. With that said, they are still large meets with several hundred men and women competing. Most of the eight weight classes for each gender had two sessions, an “A” and a “B”, allowing for a smoother, more functional schedule. Being the first session of the day, we had zero risk of things running behind.

My session (Men’s 105kg “B”) was set for Sunday morning at 8:30am. The national meet actually began Friday with the lighter men and women competing in an ascending fashion based on body weight. Now, national meets are exclusive in nature. Athletes who desire to compete at that level need to hit a qualifying total within the qualification period. With that said, they are still large meets with several hundred men and women competing. Most of the eight weight classes for each gender had two sessions, an “A” and a “B”, allowing for a smoother, more functional schedule. Being the first session of the day, we had zero risk of things running behind.

With such an early start time, I was up around 5:45am. I packed my breakfast, my snacks, some coffee, some water, and headed to the venue. In Weightlifting, athletes are given a two hour “weigh-in” prior to competing. This can cause stress for some athletes, however I’ve never really needed to cut or loose mass, consistently resting around 102-104kg bodyweight. Trust me, I know how lucky this makes me.

The Westin Lombard Yorktown Center was a great venue for the meet. Everything was fairly centralized, keeping the walking to a minimum (remember… sloths). Once weighed in, Michael and I sat in the lobby as I digested a breakfast of four hard boiled eggs, about 4oz of grilled steak from dinner the night before, and some yogurt with granola. I don’t get too ritualistic with pre-meet feedings. If it’s available, I usually try to eat a Chipotle because the macros are fairly balanced, but the chief need for me personally is hydration. The perception of weakness that can be experienced when the body is dehydrated has played with my mind before so I usually run through 30-50oz of water before and during a competition. Food and water on board, it was time to start warming up!

For a few weeks now, I’d been practicing some visualization of my warm ups and my lifts on stage. Even so, mental imaging can only assist you in executing. Once there in person, you still need to make the attempts and follow the plan. It was time to go to work.

The platform from an athlete’s perspective.

Warm ups went swimmingly. Each addition of weight was exactly what I expected it to be. Michael and I usually discus opening attempts based off what I’ve taken and felt 100% confident with in the weeks leading up to a meet. Nationals was no different. I’d hit 130kg in training one or twice in the last month and a half, performing 120-125kg countless times. To that end, we strategically selected 129kg as a solid snatch opener as it was comfortably in my range and helped us get on the board before a bunch of guys wanted 130kg (more on that in a moment).

Michael and I in the back room warming up for ’16 Nats in Salt Lake City, UT

Over the years, Michael and I have developed a pretty no-nonsense demeanor in the back room. Michael picks all the warm ups and determines when I take each warm up, with the understanding that it is my responsibility to execute. Cause, effect, cause, effect, until the performance is complete. At the local level, this job is easy. The outcome of a smaller Weightlifting contest might be separated by wider spread — say, ten’s of kilograms. Nationally, as the big fish all come to swim in the same pond, knowing how to play the numbers an absolute necessity.

We knew 130kg was going to be a very popular opening attempt in the snatch, as was 135kg. This was no secret as each athlete has to openly declare their first attempts for both lifts. For me to open at one of those numbers was to relinquish control of the flow of competition. If five guys want 130kg and my lot number (an integer randomly assigned at weigh-ins) puts me fourth of those five, I am at the mercy of fellas one through three missing their opener or moving their opener up — both common realities in the competitive environment. In the best of circumstances, your warmup is never sped up, or slowed down, based off the competitors around you. A missed lift might slow the competition down, but even more dangerously, a moved opener could put you out on the platform before you’re properly warmed up to perform the attempt (a devious strategy all good coaches employ now and again).

Sure enough, warmups were done, I made my jumps with confidence and it was time to walk out on the national stage for the third time in my Weightlifting career.

Maybe it’s different for others, but there’s not much going on between the ears when I take a competition lift. As I hear the announcer inform the loaders, “Please take the bar to one hundred and twenty nine kilos” Michael gives me a, “Let’s go! Chest up, full foot” cue. Don’t get me wrong, I’m still conscious. I hear my daughter cry out (perfect timing girl…), my family cheer my name, and the announcer say, “Here’s Taylor Gish from MSP Fitness Weightlifting Club with his first attempt.” After that, I grasp the bar, establish my hookgrip, find my focal point, and follow the same technique I’ve performed countless times in the gym. Breathe, straighten, go! 129kg was slightly rocky — but, whew! I made it! One down, two to go.

Maybe it’s different for others, but there’s not much going on between the ears when I take a competition lift. As I hear the announcer inform the loaders, “Please take the bar to one hundred and twenty nine kilos” Michael gives me a, “Let’s go! Chest up, full foot” cue. Don’t get me wrong, I’m still conscious. I hear my daughter cry out (perfect timing girl…), my family cheer my name, and the announcer say, “Here’s Taylor Gish from MSP Fitness Weightlifting Club with his first attempt.” After that, I grasp the bar, establish my hookgrip, find my focal point, and follow the same technique I’ve performed countless times in the gym. Breathe, straighten, go! 129kg was slightly rocky — but, whew! I made it! One down, two to go.

As I mentioned above, in national competitions, lifters are so closely packed that an athlete could be waiting quite sometime before coming out again. This wait period can be nice as it allows you to calm back down and catch a mental break before the next lift. On the other hand, as is more often the case, too long of a rest and you run the risk of cooling down. Michael informed me that we were going to have too much time to just sit and I was to head back to the warm up area and take a few snatch pulls at 100-110kg on his indication. I stayed fresh as five to ten minutes passed. Soon enough it was time for my second attempt at 133kg.

For Michael and I, what goes on the bar after first attempts is a combination of what Michael sees and how I feel. In the case of my snatches, a four kilogram bump was agreed upon and I took the stage once called. 133kg felt much better than ’29, but I must say, the bar felt heavy in my hands as I pulled it off the floor. Despite my perception, 133kg was a good lift, earning three out of three white lights from the judges. If you didn’t know, Weightlifting is a subjective sport left to the decision of three main referees and a back up jurors panel. Upon the athlete’s completion of the lift, the call is a simple one: red lights for a no-lift according to known rules and standards, or white lights for a good attempt.

Based of how things looked, we determined that a three kilogram push to 136kg was smart, putting a would-be PR (personal record) tie on the bar. As before, some routine snatch pulls were needed between this second and final attempt in the snatch. Whether I was physically or mentally unready I cannot say, but I do know there were inklings of doubt in my mind whether I had ’36 in me that day. Anyhow, my last attempt in the snatch was a miss. It was time to shrug it off and focus on clean and jerks.

Until next time 136kg…

The clean and jerk (sometimes referred to as clean, jerk, or simply c&j) is the final contested movement of the meet. Signaling a countdown to the first c&j, a ten minute clock is started after the final competitor of the session completes their last snatch. As it was in my snatch warm ups, cleans felt like a breeze — I’d say, arguably stronger and snappier too. When you get a couple of lifts on the board, there are never as much nerves leading up to jerks like there are for snatches. Likely assisting with my perception of strength and speed was the consumption of a little snack: remnant yogurt, remaining granola, an Epic Bar I packed along, and a few swigs of coffee (more because it sounded tasty than any ergogenic aid).

During clean and jerk warm ups, Michael was counting the attempts of other competitors ensuring we were tracking on time to first attempts. He’d touch back in with me, giving little cues like, “legs” and “come on, punch”. Nothing he hasn’t uttered a hundred times over. Complexity is paralysis this late in the picture. Keep it stupid simple so they say.

My opening attempt in the clean felt great at 163kg. At that point, I had established a total — now it was time to build. For some, making large, heroic jumps is a strategy that works for them. If you are trying to move up in international team rankings, jump to the next USAW stipend level, or just really feel ready, the benefit of loading the bar with your top-end weight is that you get multiple shots at it. Since none of those apply to me, we more often elect to take stair-stepping attempts. With that said, a five kilo push to 168kg would put me in position to take a whack at a one kilogram all time PR in the c&J of 173kg. I just had to make ’68 first.

2nd attempt: 168kg

With relative ease, 168kg fell like a domino and my combined total now stood at 301kg going into my final jerk. Before a qualifying meet the previous October (the Minnesota Open), a 301kg total would have been a lifetime best. I was well inside a territory I could dangerously convince myself of having already had success. The tough thing with final attempts in the c&j is that you must convince yourself you need it. It’s the last of six lifts, and the most missed attempt out of all lifters both nationally and internationally. Would walking away with a 301kg total netted me any less respect from my coach? My gym? My family? Not in the least! I graciously receive a trove of unconditional support from those parties. No. I had to do this for me and me alone.

Just like with snatches, we had to wait. Many athletes wanted to take shots at lifts between ’69 and ’72 before I was to be called at 173kg. I took a few clean pulls at 160 just to stay crisp, then Michael motioned for me to come join him by the entryway to the stage.

As I took a draw of water, Michael told me we were making a change and going to 174kg. I looked up at him, probably somewhat blankly, as he said, “I want to take you to ’74”. As I mentioned before, not much goes on between the ears while I compete, so I was compliant as any good athlete ought to be when their coach appoints an increase in intensity. The way I saw it, Michael had his motives (motives I’d soon discover). That’s neither here nor there — we came to compete not settle — I was fully onboard. And so, I was loaded up with a two kilo PR and a new Minnesota State Record clean and jerk.

I took the stage as I always do. I visited the chalk bucket, applying a liberal dose to my palms and the front of my shoulders where the bar rests in the jerk. I walked behind the platform, taking a moment to breathe in quickly and deeply through my nose, arousing my senses. I bowed to the judges, mimicking the same nod my coach gives the referees pre-lift, as his coach did before him. Grasping the bar, as if on auto pilot, I run through the same sequence I always do. The clean portion of the lift was aggressive in a good way. It showed, as I caught the lift a little behind where I normally do. A slight adjustment and I stood with relative ease. No time to think. I gathered a breath and drove through the bar. Arms straight? Check. Elbows locked? Check, but the bar was out in front ever so slightly. Taking a small, retreating step with my front foot and a large, gaining step with my rear leg, I managed to chase the bar down and steady the lift overhead just inches from the edge of the platform. As the down call buzzed, I smiled.

Walking off the platform, Michael and I celebrated as we accomplished what we set out to do. At that point, I then discovered his intention for the last minute increase to my final clean. After some fast computing, a 307kg total positioned me one place higher against the field. Because of his fast math, we took third in the 105kg B session and fourteenth out of my weight class overall.

Wrapping Up

My favorites.

When you dedicate hours of training towards an endeavor, let alone untold units of mental and social bandwidth, your feelings upon finishing resonate much more with fulfillment than unadulterated elation. While there is joy found in the testing of one’s abilities, I feel more satisfaction in the realization of a longterm plan. Since the onset of children, my pursuits now have a legacy component that I cannot deny when encapsulating the experience. Staying diligent to a task, honing a craft, and seeing trials through to their completion are things I hope I am displaying to those around me. Even though I frustratingly fall short, I earnestly seek to find gratification in the process of training and competing more than the direct outcome of it. Or, as a friend and patron of the gym put so eloquently in the week after the meet, “living a life well lived.”

Acknowledgements

As it is said, “It takes a village”. Here’s mine:

Ally: There’s not enough words. Thank you.

My Family: Mom and Dad bought me a membership to the Lincoln Racket Club back home in Nebraska when I was fifteen. Everyone starts somewhere, even if it’s bicep curls. Thanks for nearly three decades of support.

My Coach: A teacher through and through. I’ve learned so much and yet have so much more to grasp. Thank you Michael. Time to get back to work.

MSP Fitness: You tuned into the livestream, you asked yourself, “what on earth is this sport”, and you stuck around regardless. You are the best people to work with.

USADA: The United States anti-doping agency. This year’s nationals was my first time peeing in a cup and Bill did a fantastic job watching. For real though, Bill was a superstar and the process was exceptionally professional.

For all of your own curiosity and potential enjoyment, I thought I’d include some video links. You’ll see a link to my own performance, as well as the works of other, more stellar athletes. The 2017 USA Weightlifting National Championships in Chicago, IL certainly were nothing short of great. Highlights include:

- Video footage of my lifts.

- D’Angelo Osorio (M 105) – 211kg Clean and Jerk [D’Angelo’s 22 years old and one of America’s best lifters in my weight class]

- Jessica Lucero (W 58) – 116kg Clean and Jerk [An American record and double bodyweight!]

- Mattie Rogers (W 69) 134kg Clean and Jerk [American record and the 30th of 30 made competition lifts IN A ROW!]

- Colin Burns (M 94) 170kg Snatch [Best overall Men’s lifter with the easiest looking 374lb snatch]

- Click HERE for full RESULTS.